Was there really a Mafia boss of bosses in America? A man more powerful than Al Capone, Lucky Luciano or Meyer Lansky?

Salvatore Maranzano was so powerful he could compose an execution list that included the names of Luciano, Frank Costello, Vito Genovese, Joe Adonis, Willie Moretti, Dutch Schultz and the “fat guy” in Chicago, Capone. Maranzano could do all this because he was the boss of bosses. He said so himself.

Unfortunately, Maranzano’s reign came to a violent end after only four months. After that, despite the earnest efforts of enterprising journalists, the Mafia boss of bosses title was relegated to the scrap heap. Organized crime was more powerful than any so-called superboss. In that sense Maranzano died a fraud; still, he was one of the most important personalities in American crime. He founded, if we are to completely trust informer Joe Valachi, what was to be known as the Cosa Nostra.

|

Maranzano was an old-line mafioso, holding to the crime society’s tradition of “respect” and “honor” for the family boss and continuing the blood feuds with enemies of decades past. But he did have modern ideas about crime and wanted to institutionalize it in America—with himself on top. If he had survived the bloodletting of the early 1930s, organized crime may well have had a different look today.

When Maranzano initially came to the United States is not certain. It appears he was here in 1918, again in 1925, and once more in 1927, and it’s possible he moved in and out of the country several times before settling here in 1927. At that time Maranzano was sent by the most powerful Mafia leader in Sicily, Don Vito Cascio Ferro, specifically to organize the American crime families, even non-Italian ones, under one leadership.

Don Vito, who had been in America in earlier decades, apparently saw himself heading such an organization, and apparently Maranzano was content to be his most favored follower. However, shortly after dispatching Maranzano, Don Vito was arrested by the Fascists and put in prison for the rest of his life. That left Maranzano on his own.

Maranzano surrounded himself with gangsters who had emigrated from his hometown in Sicily, Castellammare del Golfo. By 1928 he had attracted so many supporters that the foremost Mafia boss of New York, Giuseppe “Joe the Boss” Masseria realized he was a danger. A cunning adversary, Maranzano— college educated and originally a candidate for the priesthood—indeed intended to depose Joe the Boss and so exploited the idea that Masseria hated all Castellammarese.

Joe the Boss was a glutton in personal habits as well as in his administration of criminal activities. He demanded that other mafiosi pay him enormous tribute. Maranzano cultivated the resentment this stirred up in Masseria’s subchiefs and he worked on winning defections by promising a fair division of loot.

|

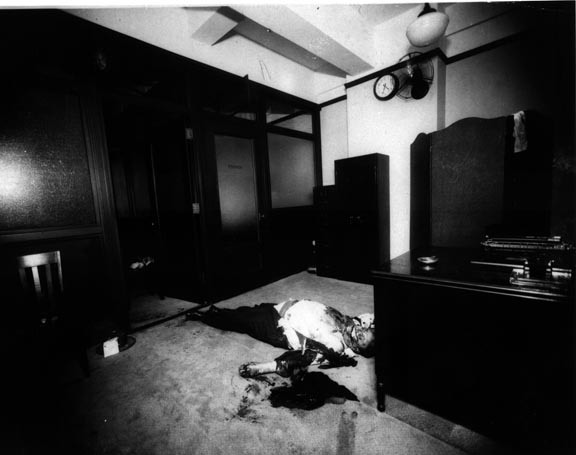

| The dead of Salvatore Maranzano |

Maranzano particularly tried to lure away Lucky Luciano who had by that time become one of Masseria’s most valuable aides and had reorganized gang activities for maximized profits. Luciano, however, resisted Maranzano’s overtures, having plans of his own.

To check Maranzano’s growing strength, Joe the Boss finally declared war. Masseria could field a few hundred more gunners than Maranzano and was confident he could crush him. From 1928 to 1930 the death toll between the two camps probably exceeded 50. The police were handicapped in trying to get a count; it was hard to tell which corpse belonged to the Castellammarese War (as the conflict was known) and which to the ordinary booze wars raging in the underworld.

As the Castellammarese War continued, it took on a third dimension. Luciano was cultivating younger gangsters on both sides with his ideas for an entirely different crime setup. His would ally the Italian criminals with powerful Jewish mobsters into a syndicate that would slice up the crime pie fairly and would even make the pie bigger. What impressed many young mafiosi was that Luciano, through Frank Costello enjoyed excellent relationships with important elements in the police and in politics. He offered far better protection than either Joe the Boss or Maranzano. Luciano soon was in a position to know what each chief was up to, having secret supporters spying for him in both camps.

|

For years Luciano had been close to Jewish mobster Meyer Lansky who he regarded as the most brilliant criminal mind in the country; their original plan was for Lansky to line up the Jewish mobsters around the country and Luciano the various Italian elements. Lansky had the easier chore, all but a few important Jewish mobsters saw the virtues of a national crime syndicate.

Among the Italian crime families, Luciano had to proceed more cautiously. The pair decided the safest course was to let Masseria and Maranzano weaken each other with continual bloodletting until one or the other perished. Then as the Luciano/Lansky team gained strength, they would strike the remaining old don.

However, by 1931 Masseria and Maranzano were still at it. Maranzano gave far better than he got, but he was not yet the victor. Fearful that Maranzano would accumulate too many supporters as the conflict continued, Luciano and his cohorts decided to eliminate Joe the Boss. On April 15, 1931, Luciano lured Masseria to lunch at a restaurant in Coney Island. After the meal the pair played cards while all the other patrons cleared out. Then Luciano went to the men’s room. While he was gone, four assassins rushed into the establishment and laid down a fusillade of 20 bullets. Masseria was struck six times and was dead when Luciano strolled out of the men’s room.

Luciano then declared peace with Maranzano. Maranzano was pleased and, in supposed gratitude, made Luciano his number one man in his new organization. In a remarkable conclave, he summoned 500 gangsters to a meeting in the Bronx and outlined his grandiose scheme for crime. The New York Mafia would be divided into five major crime families, each with a boss, a sub-boss, lieutenants and soldiers. Above all the five families would be a “boss of bosses.” That was Salvatore Maranzano. Maranzano dubbed this new organization Cosa Nostra, which really meant nothing more than “our thing.”

All would be peaceful and profitable, he asserted. Secretly though, Maranzano did not believe that. He rightly gauged Luciano’s great ambition, and realized that by dealing with non-Italian mobsters, Luciano was creating his own power base, one that would soon threaten Maranzano. He also knew that Luciano still commanded the loyalty of many important men within this new Cosa Nostra. He composed a death list of top mobsters who had to be eliminated. The list included Luciano, Costello, Genovese, Adonis, Moretti, Schultz and Chicago’s Capone, who had been friendly with Luciano for years.

Maranzano knew it would not be easy to kill all these men and he decided not to risk all-out war before at least some were eliminated. Otherwise, he could not be sure who was on whose side and who might betray him to Luciano. Maranzano decided to have the job handled by non-Italians so that he could pose as innocent. He recruited the notorious young Irish killer Vince “Mad Dog” Coll and arranged for him to come to his office in the Grand Central building at a time when Luciano and Genovese would be present.

Apparently Coll was to kill the pair that day and “lose” their bodies so that he could knock off as many of the others as possible before the murders became known. Maranzano gave Coll $25,000 as a down payment and promised him $25,000 more on the elimination of the first two victims.

However, Luciano got wind of the assassination plan and knew the murder operation would start when he got a phone call summoning him to Maranzano’s office. Luciano, through Lansky, already had his own murder team in training with a plot to kill Maranzano. He ordered that training speeded up. On September 10, 1931, Maranzano telephoned.

Shortly before Luciano and Genovese were slated to arrive at Maranzano’s headquarters, Tommy Lucchese walked in. Maranzano was unaware of Lucchese’s link to Luciano. (In fact, Lucchese was Luciano’s main spy inside the Maranzano organization even before Masseria’s murder.)

Shortly after Lucchese arrived, four men walked in flashing badges and announcing they had questions to ask Maranzano. The four were Jewish gangsters Luciano had borrowed for his counterplot since Maranzano did not know them. They also did not know Maranzano which was why Lucchese was present—to make sure they got the right man.

The bogus officers lined up Maranzano’s bodyguards against the wall and disarmed them. Then two went into Maranzano’s office and stabbed and shot him to death. The assassins and Lucchese charged out. So did the bodyguards when they found that their boss had been executed. On the way down the emergency stairs, one of them ran into Mad Dog Coll coming to keep his own murder date. Informed of the new situation, Coll turned and left whistling. He was $25,000 to the good.

Maranzano’s death had far-reaching effects on organized crime in America. Essentially, it marked the end of the Italian Mafia in America. What remained was a new American Mafia that would become part of a national syndicate with other ethnics, something the old Mafia was too rigid to allow. Luciano immediately eliminated the post of “boss of bosses” and called the new organization the “combination” or “outfit” or as a sop to the traditionalists among the mafiosi the “Unione Siciliano,” a corruption in spelling of the longtime Sicilian fraternal organization.

The concept of “Cosa Nostra” died as well with Maranzano, not to be revived by federal authorities and a cooperative Joe Valachi until the early 1960s, as a way to get J. Edgar Hoover out of a deep hole. For decades he had denied the existence of the Mafia and organized crime, but now he could announce with a straight face that the FBI had been studying the “Cosa Nostra” for a long time. Thus even when he was partially right he was 30 years behind the times.