In 1928, a University of Chicago graduate, 26-yearold Eliot Ness, was put in charge of a special Prohibition detail set up to harass the Capone gang. The local police and regular Prohibition agents were incapable of doing so since most, if not all, were on one or another of Capone’s bribe payrolls.

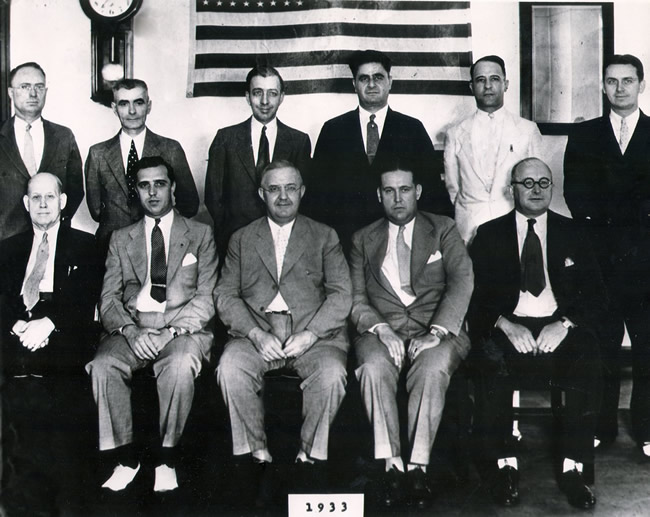

Ness set about assembling a squad of nine agents who would be “untouchable,” or unbribable. Meticulously, he went through hundreds of files until he came up with nine agents—all in their 20s—who had “no Achilles’ heel in their make-ups.” Incorruptible, they also were experts in varied activities helpful in fighting bootleggers—wiretapping, truck driving and, above all, marksmanship.

When the detectives moved into action, the underworld soon found them to be dedicated to their task, defiant of all threats and violence and unresponsive to cash payments. It was the underworld, stunned to find lawmen of the period who could neither be bought nor frightened, that dubbed Ness’s men the “Untouchables.”

|

The Untouchables are now a part of American criminal folklore. Latter-day television, in a show called The Untouchables, attributed much more credit and impact to them than they deserved, insisting they practically brought the Capone organization to its knees. Actually, their frequent raids of mob stills and distribution centers did cost the Capones a considerable amount of money but hardly caused Chicago to dry up—despite the claims of Ness at the time and his enthusiastic biographers then and now.

Ness thrived on personal publicity and always informed the press whenever a major raid on a brewery was in the works. The army of photographers who descended on the site frequently got in the way and sometimes even caused a raid to be bungled, but Ness’s superiors were pleased.

The publicity he produced proved that the Capone gang was not invulnerable. And Ness did provide a sort of smokescreen, distracting Capone while other federal agents infiltrated his organization to come up with tax evasion facts that eventually sent America’s greatest gangster to prison.

|

| The Untouchables |

After the fall of Capone, Ness continued warring on Prohibition violations in Chicago and, later, in the “moonshine mountains” of Tennessee, Kentucky and Ohio.

Although his Chicago exploits are best remembered, Ness’s most impressive work against organized crime took place in Cleveland, Ohio, where he was named public safety director in 1935 by a reform city administration. Cleveland at the time was as corrupt a big city as any in the nation, its police force notorious for being “on the pad,” taking underworld graft. Builders couldn’t operate in the city without paying off labor racketeers.

A vicious gang called the Mayfield Road Mob, Jewish and Italian criminals working in profitable harmony, strangled and blighted virtually every neighborhood with gambling, bootlegging and prostitution rackets. Violence was common on the streets, and gang killings and the one-way rides were about as prevalent as they were in Chicago. Given a free hand, Ness knew that if he was to create a new environment in the city he would have to reform the police department. He ordered mass transfers and fired officers for taking bribes or being drunk on duty.

During his six years on the job, Ness himself was the object of shootings, beatings, threats and even an attempted police frame-up. But in the end, Ness was able to carry out what was called his “Midwest Mopup,” transforming Cleveland, in the words of one crime historian, “from the deadliest metropolis to ‘the safest big city in the U.S.A.’” The Mayfield Road Mob was crushed, and such syndicate leaders as Moe Dalitz were forced to move their gambling operations to outlying counties, and, eventually, because of continuing pressure, into northern Kentucky.

During World War II, Ness served as federal director of the Division of Social Protection for the Office of Defense, cracking down on prostitution and venereal disease around military establishments and vital production areas throughout the country. After the war, he worked in private business until his death at 54 in 1957.